This article, prepared for the Appraisal Institute of Canada (AIC) and published in the Canadian Property Valuation Magazine, discusses the concept of financial leverage (debt) and how business risks and financial risks are addressed from a valuation perspective.

Members of the Appraisal Institute of Canada (AIC) are frequently asked to value real property for mortgage financing purposes. Real estate is appraised free and clear of mortgage financing; however, the current or anticipated amount of debt secured by a property impacts the financial risk accepted by a property owner and, by extension, the risk borne by the appraiser should the property owner default on the loan.

Valuation theory states that all else equal, the rate of return demanded by an equity investor will increase as financial leverage increases. This means financial risk, defined as “risk related to the use of debt to finance an investment”, increases as an investor uses more and more debt.[1] Accordingly, a prudent investor will demand a higher expected rate of return as compensation for accepting incremental financial risk.

Valuation theory also states that, except for the tax benefit arising from the tax deductibility of interest expense on debt, value cannot be created (or destroyed) by simply changing an asset’s capital structure. Stated differently, “The change in financial structure does not affect the amount or risk of the cash flows on the total package of the debt and the equity” and therefore “the market value of any [property] is independent of its capital structure”.[2] Be that as it may, appraisers must remember “the transaction price for one property may differ from that of an identical property due to different financing arrangements[]” and thus “appraisers must make sure that cash equivalency adjustments reflect market perceptions” when this is the case.[3]

How much, if any, debt a property owner chooses to use in a particular situation depends on numerous factors, including but not limited to:

- The type, location, age, condition and use of the property;

- The property’s historical and, more importantly, anticipated cash flows;

- The property owner’s investment strategy, risk tolerance and financial resources; and

- The availability, terms and cost of debt, including the covenants that, if breached, will cause the loan to be in default.

In contrast to financial risk, the terms market risk, operating risk, and business risk are used broadly to describe shifts in supply and demand, changes in laws and regulations, fluctuations in capital markets, and other operational considerations. Simply put, these factors impact the amount, timing and perceived risk(s) of the expected benefits (i.e., cash flows) anticipated from a property, irrespective of how the property is financed. In other words, the unlevered (also known as unleveraged, before-debt or debt-free) cash flows anticipated from a property are not influenced by financial risk. Rather, unlevered cash flows and the perceived risks in achieving those cash flows are affected by market risk, not financial risk, as the latter relates solely to the impacts of finance leverage (i.e., the use of debt, also known as gearing).

In theory, “any shift in capital structure can be duplicated or ‘undone’ by investors”[4] and for this reason, any financial risk a property owner chooses to accept will only impact the expected risk and return on her/his equity, not the expected risk and return on the asset as a whole (i.e., the total package of the debt and equity). Again, the caveat here is the property is not being transacted based on atypical or non-market financing.

The following case study attempts to illustrate these concepts using a hypothetical commercial property and some simplifying assumptions:

- A 2,500 sq.ft. commercial property is purchased today for $1,000,000 based on a going-in overall capitalization rate of 5.0%;

- The property owner intends to hold the property for five years with the estimated terminal value at the end of the holding period calculated using a terminal capitalization rate of 5.0%;

- There are no transaction costs at the end of the holding period;

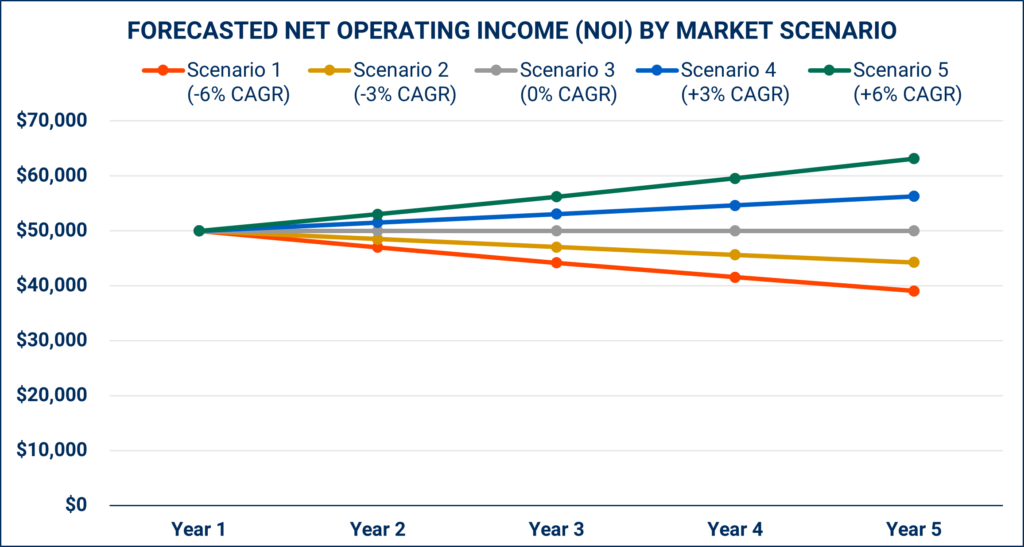

- In Year 2 and each year thereafter, the property’s Net Operating Income (NOI) is anticipated to change based on five distinct market scenarios (collectively, the “Market Scenarios” ):

- Market Scenario 1 = NOI changes at a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of -6%

- Market Scenario 2 = NOI changes at a CAGR of -3%

- Market Scenario 3 = NOI stays flat, meaning the CAGR is 0%

- Market Scenario 4 = NOI changes at a CAGR of +3%

- Market Scenario 5 = NOI changes at a CAGR of +6%

- Each of the Market Scenarios assumes a vacancy and collection loss allowance and structural allowance of 0%;

- Each of the Market Scenarios is analyzed based on three separate financing scenarios (collectively, the “Financing Scenarios” ):

- Financing Scenario 1 = No financial leverage (Loan-to-Value or LTV of 0%)

- Financing Scenario 2 = Moderate financial leverage (LTV of 50%)

- Financing Scenario 3 = Significant financial leverage (LTV of 85%)

- Financing Scenario 2 and 3 each assume the cost of debt is 3.0% and the amortization period is 25-years; and

- The income tax rate is 0% across all scenarios.

Figure 1 illustrates the property’s forecasted NOI under each of the Market Scenarios. As a reminder, NOI is calculated on a before-debt and before-tax basis, which means the Financing Scenarios do not influence NOI calculation.

Figure 1

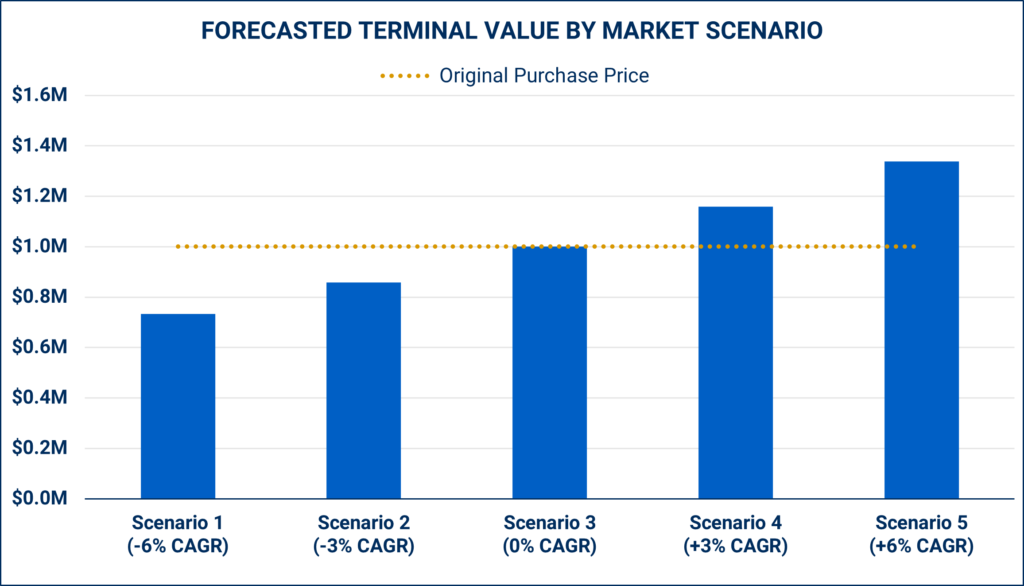

Figure 2 illustrates the property’s forecasted terminal value under each of the Market Scenarios. Note the terminal capitalization rate and NOI are “unlevered” metrics that are not impacted by financial leverage (or income tax). As such, the Financing Scenarios do not influence the terminal value calculations.

In summary, the property’s terminal value indicates a loss in Scenario 1 and 2 due to declining NOI coupled with no change to the capitalization rate. Scenario 3 results in a terminal value equivalent to the original purchase price, which some may call ‘break-even’, even though this description disregards the concept of the time value of money. Lastly, the property’s terminal value indicates a gain in Scenario 4 and 5 due to increasing NOI coupled with no change to the capitalization rate.

Figure 2

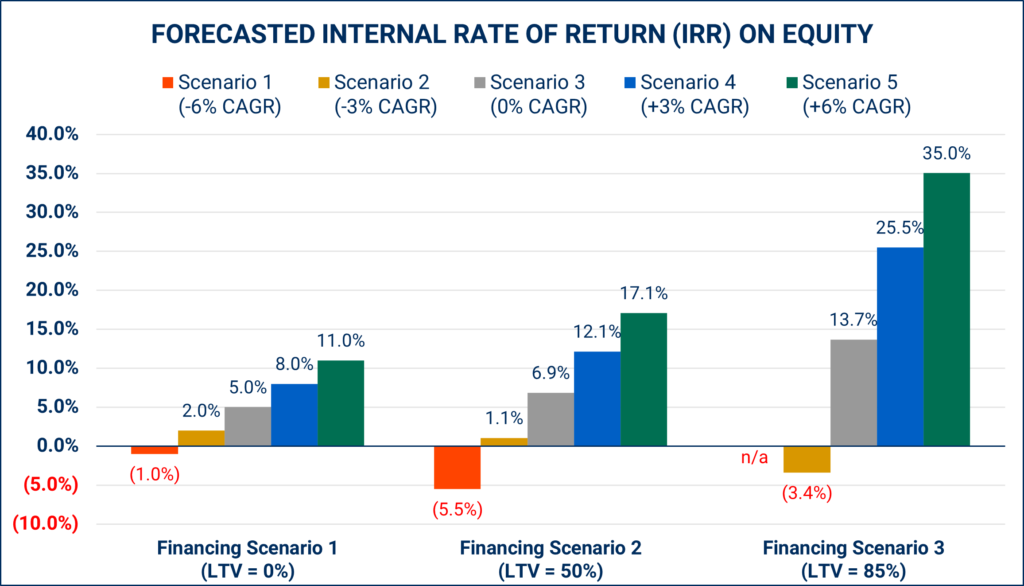

Figure 3 illustrates the forecasted Internal Rate of Return (IRR) on equity for each of the Market Scenarios and Financing Scenarios, or 15 scenarios in total (5 Market Scenarios x 3 Financing Scenarios = 15 scenarios in total). This analysis illustrates the following:

- The IRR on an unlevered basis (i.e., no financial risk) ranges from a low of -1.0% to a high of 11.0%, depending on the particular Market Scenario;

- The addition of financial leverage in Financing Scenario 2 results in the IRR range for the Market Scenarios to widen, from a low of -5.5% to a high of 17.1%; and

- Increasing financial leverage to 85% LTV under Financing Scenario 3 results in an indeterminate IRR on the low end (more on this later) and 35.0% on the high end.

In simple terms, Figure 3 illustrates that increasing financial leverage results in the magnification of downside risk and upside potential.

Figure 3

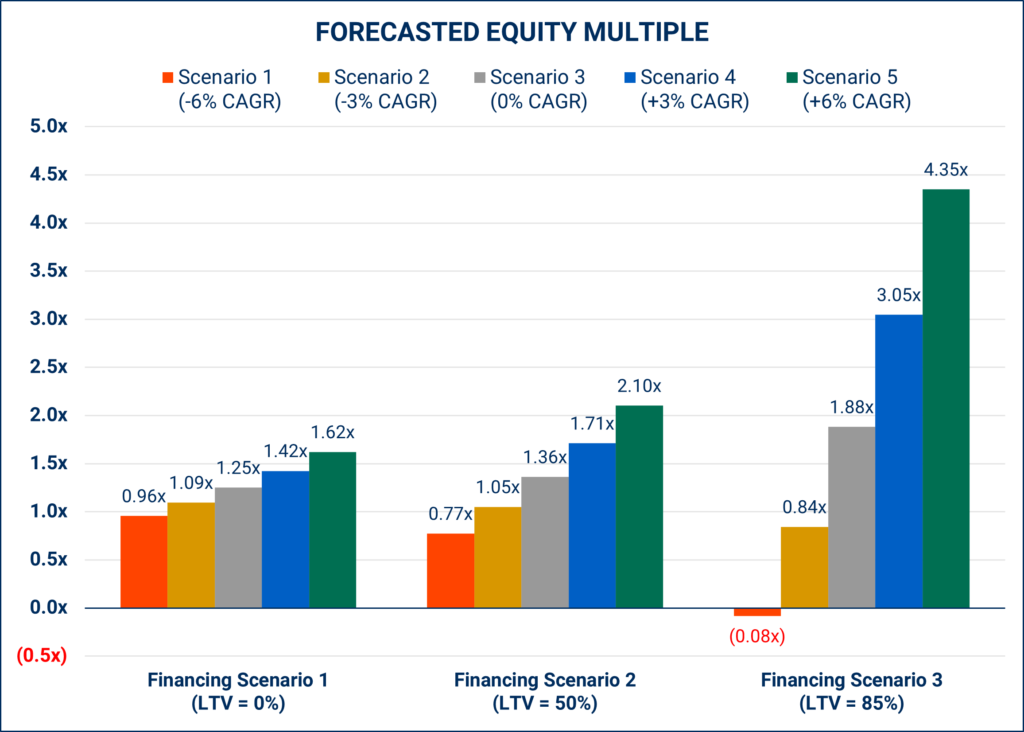

Figure 4 illustrates the forecasted equity multiple for each of the Market Scenarios and Financing Scenarios. The equity multiple is calculated by dividing the total equity cash flows from an investment by the investor’s initial equity contribution. The equity multiple does not account for the time value of money, the risk profile of the income stream or the duration of the investment horizon; however, it does provide a relatively simple metric that answers the question “How many dollars will I get back for each dollar I invest?”. An equity multiple greater than 1.0x indicates the investor will receive more than s/he invested, while an equity multiple lower than 1.0x means the investor will receive less than her/his initial investment. A negative equity multiple indicates the investor will lose more than the amount s/he originally invested.

As noted earlier, the combination of Market Scenario 1 and Financing Scenario 3 results in an indeterminate IRR. The property’s poor operating performance (i.e., declining NOI) coupled with high financial leverage (i.e., LTV=85%) in this particular scenario creates a situation where the equity investor suffers a loss beyond her/his equity initial investment. In other words, there is no IRR in this scenario because the definition of IRR cannot be satisfied, meaning there is no “discount rate that makes the net present value of all cash flows equal to zero.”

Figure 4 illustrates the combination of Market Scenario 1 and Financing Scenario 3 results in an equity multiple of negative 0.08x. This means the investor would suffer a total loss of her/his $150,000 initial equity investment ($1,000,000 financed at 85% LTV = $150,000 equity investment), and an additional loss of roughly $12,000 ($150,000 initial equity investment x equity multiple of negative 0.08x).

Figure 4

In summary, appraisers are well-positioned to assist their clients in evaluating the risks and rewards of using financial leverage in real estate transactions. Members of the AIC preparing appraisal reports for mortgage financing purposes can reduce their exposure to risk by following best practices such as naming the authorized lender in their appraisal report. In some cases, it may be appropriate for the appraiser to limit the type and amount of financing (i.e., first mortgage financing up to 75% LTV) for which she/he is willing to accept liability.

[1] The Appraisal of Real Estate, 3rd Edition, Editor: Larry Dybvig, Appraisal Institute of Canada, c2010, p. 5.6

[2] Brealey, Richard A., Stewart C. Myers, and Franklin Allen. Principles of Corporate Finance. New York, NY: McGraw=Hill/Irwin, 2006.

[3] The Appraisal of Real Estate, 3rd Edition, Editor: Larry Dybvig, Appraisal Institute of Canada, c2010, p. 14.11

[4] Brealey, Richard A., Stewart C. Myers, and Franklin Allen. Principles of Corporate Finance. New York, NY: McGraw=Hill/Irwin, 2006.